You are here

The adaptation process

Coastal Climate Adaptation Decision Support (C-CADS)

Step 2: Assessing Risks and Vulnerabilities

Assessing risks and vulnerabilities to climate change will help to create a risk register to support identifying and planning adaptation options.

At a glance

- You are now in a position to determine your vulnerability to climate change and identify the risks you may need to address.

- This section explains how to do this and to account for the capacity of your organisation and/or your stakeholders and community to address potential impacts from climate change.

- This stage requires consideration of the risks that are likely to occur and what thresholds can be identified and monitored, to indicate that a particular risk must be managed.

- Creating or updating a risk register can help to start to identify potential adaptation options.

Main text

Purpose

In this step you will:

- develop an approach for your risk assessment and reporting that is fit for the challenge faced and for the purpose of your organisation, and that will support adaptation planning and action

- understand the adaptive capacity of your organisation and stakeholders, and importantly

- have a good understanding of whether and when to act

- have an evidence base to help you with your internal and external engagement activities.

Introduction

At this stage you have garnered support to develop an adaptation plan from senior management and elected officials (board or council). You have begun to engage with internal colleagues and with other relevant organisations. You have established advisory groups or committees—or begun to canvas ideas amongst established community groups— that are required to support your adaptation planning and implementation. It is now possible to begin to develop a detailed adaptation strategy or plan.

Through your first pass risk screening, you have developed an outline of risks highlighting vulnerable decision areas/systems/assets of your organisation. This has also helped you to determine the scale at which you need to focus, and the stakeholders (internal and external to your organisation) you need to get on board for risk communication and adaptation planning.

Now, to develop an adaptation plan, you need to acquire a more detailed knowledge of the vulnerabilities and risks that face the shortlisted decision areas/systems/assets of your organisation. This involves conducting a risk workshop with relevant stakeholders to understand potential impacts (direct and indirect) in greater detail and explore your organisational capacity to tackle them. Depending on your decision context, you can use a second pass or a third pass risk assessment approach described in Guidance on risk assessment. Ultimately, understanding your risks in greater detail will underpin how you determine appropriate management actions to adapt.

Before conducting any further risk assessment, you should also be aware of any climate risk action that your organisation and stakeholders might have planned or undertaken. This will underpin your planning activities as well as discussions with stakeholders about their appetite for climate-related risk—or how much risk they are willing to endure—and therefore the level of action that is required.

Establish the type and level of risk assessment methodology to be used

There is a variety of approaches that can be used for risk and vulnerability assessment and your choice largely depends on your current point in your adaptation journey. See CoastAdapt content Guidance on risk assessment to get an overview of three different types of risk assessment approaches and their appropriate context of use.

In general, if resources are low and it is difficult to obtain the necessary funding to undertake a detailed risk assessment (a second or third pass), you can use the results of your first pass risk screening for high-level adaptation planning. Alternately, you can redo the first pass screening with more detail for your short-listed decision areas/systems/assets if further detailed information is available. If you choose not to invest in a more detailed risk assessment (i.e. a second pass or a third pass), it is important to recognise that this increases the likelihood that your assessment may not be accurate, and you may not have the right amount of information necessary to develop an appropriate plan. It is then possible that you might make poor recommendations or decisions that may have adverse consequences when implemented. You will need to clearly document the reasons why you have not taken this step, including any scientific, social or economic rationale. This may be required in the future if any adaptation/management decisions are questioned by stakeholders such as the community, or Boards, or in the courts. You may want to read CoastAdapt content on Implications of taking no action.

Figure 1: The three-tier climate change risk assessment process. Source © NCCARF

Your first pass risk assessment may identify that you do not have any major climate risk to your interests at this stage. This is not highly problematic as long as you identify a series of indicators of climate change and associated impacts that can be measured over time. You need to evaluate these at predetermined time steps to assess your risk from climate change. More information on establishing indicators and on climate adaptation pathways can be obtained from Identifying indicators and a Pathways approach.

On the other hand, if the first pass risk screening suggests that climate change effects span across different sectors of your organisation, and are likely to be significant, then you should consider undertaking a second pass risk assessment. Note that down the track in your adaptation journey you may require a third pass risk assessment, for instance if your organisation considers implementing a project to protect a particular system or asset which is at high-risk but critical for your organisation’s business operations. Second and third pass assessments require more detailed information about the relevant risk (extent and rate of change) to enable you to make sound decisions (e.g. when to invest, engineering design of options). This includes detailed modelling or hazard studies which are generally resource intensive. General guidance is available in CoastAdapt for conducting a second or third pass assessment in Guidance on risk assessment. In many cases it is best to use expert consultants to undertake this process and we suggest how to make best use of consulting services for climate change related projects in Working with consultants. Spending money wisely at this stage may reduce spending at a later stage, and enable options to be identified that are fit-for-purpose.

Now we discuss some fundamental concepts and broader issues around risk and vulnerability assessment which should help you to understand the overall process and its relevance in the broader context of adaptation planning. For more detailed guidelines for conducting a second or third pass assessment see Guidance on risk assessment.

Use existing risk assessment approaches

Most organisations have risk assessment and reporting approaches that are embedded in organisation management processes. In undertaking climate risk assessments it is useful to consider the current practices and then use or amend them where possible. This is likely to make your job easier when reporting risks, and seeking support to manage them.

Refine your priority areas of interest

You have decided on the initial scope of the adaptation planning in the previous step of C-CADS, including the scale at which you need to act. You should now further develop knowledge about the system and its components, and build on the information used to scope the challenge. Much of this information may already be available in other documents and plans, or can be obtained from other sources (see Waves, water levels and climate change, Estuaries and climate change, Information manual 1: Building the adaptation case, Sediment Compartments information, OzCoasts, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Geoscience Australia).

Some prompting questions include:

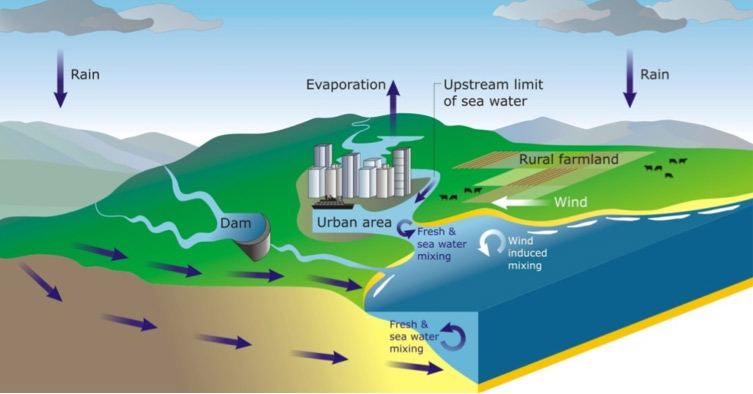

- Do you know how your estuary(ies) function?

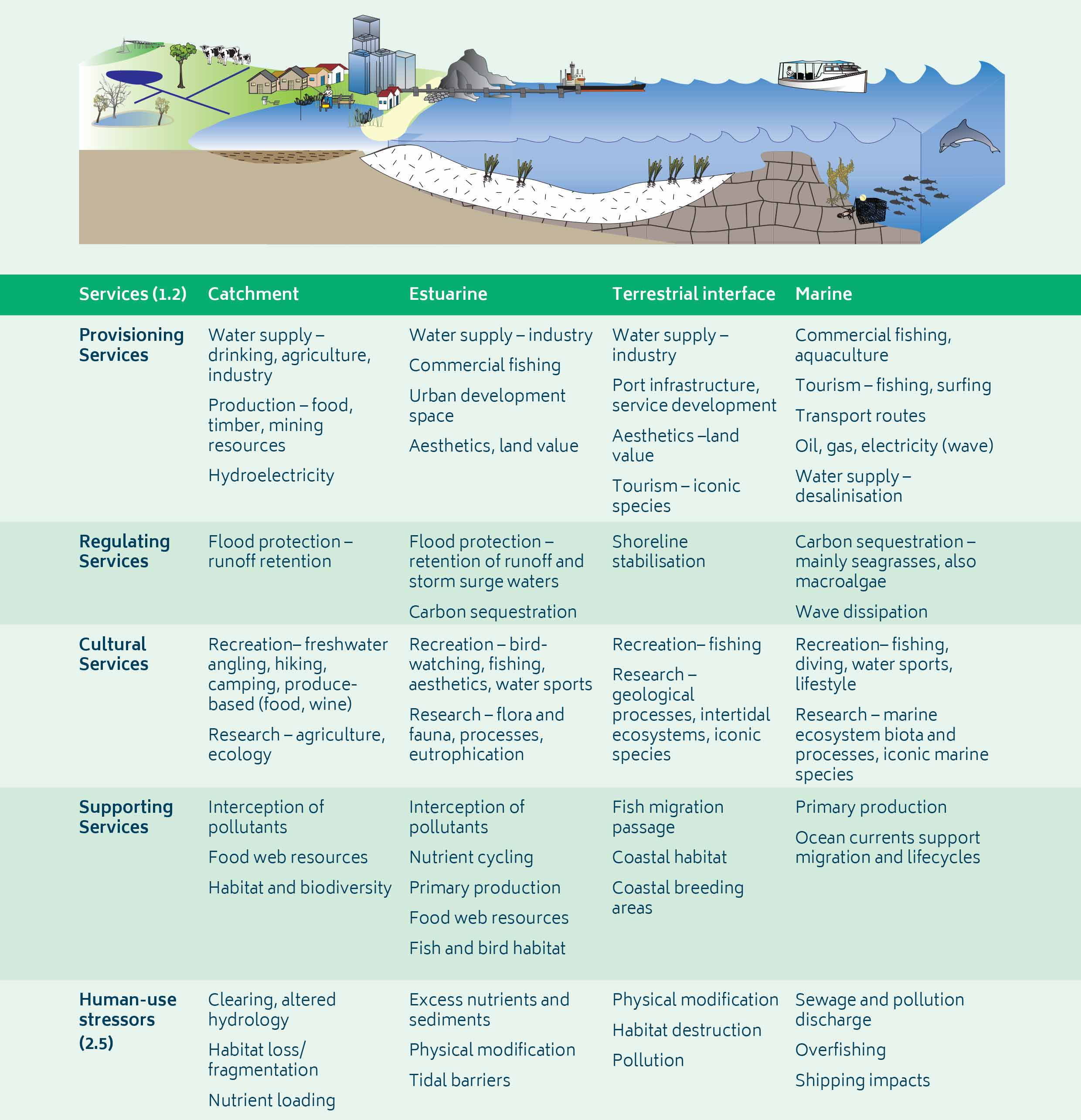

- What ecosystems services are provided by elements in your area?

- Where is critical infrastructure placed in your area of interest?

- What are the present and future demographics of your community?

- What are important features and characteristics of the area?

- Have any risk assessments of the area already been undertaken?

T4T2_Figure-4.jpg

ecosystems-table-lo.jpg

You may hire a consultant to undertake a data review and develop an understanding about your area, or to do an in-house desk top study. Information Manual 3: Available datasets provides detailed lists of available datasets and their relevant context of use. As well as listing existing datasets, section 6.1 of the manual provides a guideline on deciding when to look for better data (data needs and gap audits).

Once you have a good overview of your area of interest, you are well placed to begin your risk assessments.

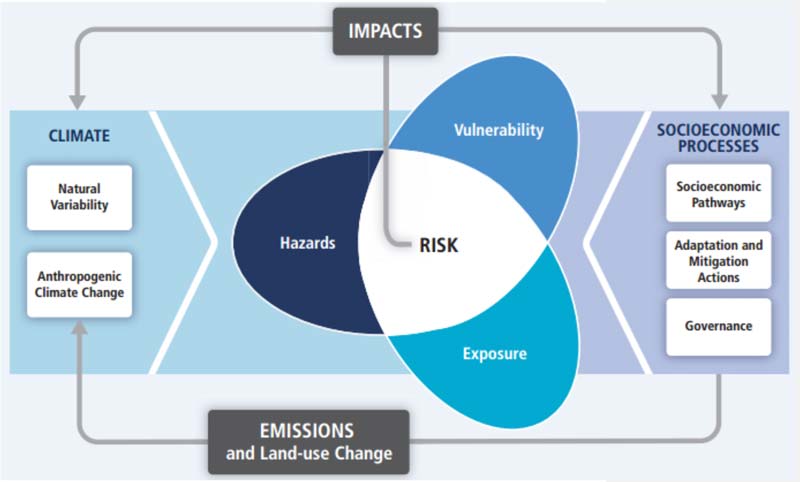

Climate change risk and vulnerability

To understand risk it is also important to understand vulnerability (Figure 4). Climate change vulnerability is defined as the propensity to be adversely affected by climate change (IPCC 2014). It encompasses a variety of concepts and elements including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and lack of capacity to cope with and adapt to future changes (IPCC 2014).

On the other hand, risk is defined as the potential for consequences where something of value is at stake and where the outcome is uncertain, recognising the diversity of values. Risk is often represented as probability of occurrence of hazardous events (likelihood) multiplied by the impacts (or consequences) if these events occur. Risk results from the interaction of vulnerability, exposure, and hazard (IPCC, 2014).

T4T2_Figure-1.jpg

Therefore, understanding the vulnerability of your business, organization or system of concern (e.g. assets, communities) can help you analyse the possible consequences of a potential hazard, which eventually will lead you to understand your risks.

Understanding risk and vulnerability of your business to climate change

Before you start conducting a second pass risk assessment you should specify your scope or the objective of this process. Answering some of the following questions may help you to clearly define your scope. You may have tackled some of these questions in your first pass risk screening in Step 1. It is worth revisiting them at this stage, now you are engaging with other stakeholders.

- What level of risk are you willing to bear?

- Which climate change scenarios should you use?

- What is your area of interest?

- What is the time span you are interested in?

- Has the area of interest been affected by present or past climate driven events such as floods, heatwaves, bushfires, beach erosion?

South-east-qld-flooding-sml.jpg

The vulnerability of your business, organisation, or system to climate change can be determined by understanding their exposure to the effects of climate related changes, and assessing this exposure against the sensitivity, and their capacity to adapt, to climate change effects. For example, a house may sit on a very low lying piece of ground and so is highly exposed to increases in sea level over time. The building materials may be intolerant to salt water, making the house highly sensitive to increased sea levels. Additionally, the house may be constructed on a concrete slab which limits its ability to be raised, and ultimately reducing its capacity to be adapted to higher sea levels in future. Therefore, high exposure and sensitivity to climate change impacts, combined with low capacity to adapt, make the house highly vulnerable to climate change.

Assessing exposure to climate risk

At this stage you should collect information about the climate change projections for your area of interest. When possible, avoid using only one projection of future climate (e.g. a specific value of sea-level rise such as a benchmark). Keep in mind that future changes in climate are really about a range of future possibilities (‘projections’), not a single best-guess possibility (a ‘prediction) (see more details in Understanding climate projections, Assessing climate scenarios, Using climate scenarios. A common approach to planning for climate change is to develop three scenarios— ‘worst-case’, ‘best-case’ and ‘mid-range’— to explore the range of possible future outcomes. This choice can also be guided by design life and/or importance of the service that your system provides. As an example, if your system has a short design life (i.e. 10 to 20 years) then it might be useful to adopt a high end climate change projection. The reason for this is that, in a short time range, there is very little difference between climate change projections; current scientific observations suggest that climate change is tracking very close to the high end of projections. However, when assessing risks to critical systems, you should try to understand the full breadth of the risk by considering longer time frames and high emission scenarios, and then prioritise risks based on your relevant decision time frame.

You should list the components of your business or organisation that may be at risk from climate change. A good starting point is to look for existing hazard studies or maps that may have been developed for your area of interest. Any areas at risk under current climate are likely to be under greater risk in a future climate. CoastAdapt visualisation provides some coastal inundation information which may be useful to get a sense of the extent of future at risk areas. However, this information is very coarse and should be used with caution and only for a first or second pass assessment. If you need higher precision for making investment decisions, or engineering design of complex projects, you may need to engage with relevant consultants to develop a hazard map that suits your specific purpose (i.e. a third pass assessment). Note that it is usually a waste of resources to do detailed risk assessments (a second pass or third pass) before some first pass efforts; this is both for technical reasons (i.e. identify where effort is needed) and social ones (i.e. identify stakeholders that need to be engaged in order to progress adaptation initiatives). Leaping into technocratic detail too quickly can be a bad mistake.

Sensitivity to climate risk

Generally, if a system is highly sensitive to climate change then it is more likely to suffer from future changes and so should be considered more vulnerable. Understanding sensitivity requires an understanding of how the projected changes in climate are likely to impact your interests. A good approach is to take the interests that you have identified as exposed and consider each of these in turn to identify how it may be impacted by projected climate changes. To support you, we provide information on impacts of climate change on various sectors (see the summary of Likely impacts by sector). If you find that projected changes are likely to impact your system components then you should consider your system as sensitive to climate change impacts.

As an example, if you are assessing risk to the storm water system of an area close to the coast and you find that a future projection suggests increased intensity of rainfall, then the current capacity of the storm water system may not handle the runoff. This would then cause some localised flooding during rain storms which could restrict access to community assets and impact private property. Therefore your storm water system should be considered as sensitive to climate change.

Understanding the general dynamics of the coastal system around your coastline of interest (e.g. sediment movement, erosion or accretion of beaches) can also help you to determine the sensitivity of your shorelines to future climate related changes. This understanding may also help you to investigate your possible adaptation options down the track. You can find more information on Sediment compartments and their associated processes.

You should also think how disruption in one system can impact others (i.e. indirect impacts). In other words, you should try to investigate if there is any interdependency among different systems. As an example, if you are assessing risk to a water supply network, then you should also try to think how performance of other connected and nearby infrastructure such as electricity, roads may impact on the operation and maintenance of your infrastructure and vice versa.

Adaptive capacity

Once you understand the potential impact of climate change on your asset/area of interest, you need to consider the capacity of your organisation, its assets, and/or members of the community to respond to these impacts. This is known as adaptive capacity. A combination of adaptive capacity and potential impact will determine the vulnerability of an organisation to climate change.

Adaptive capacity depends on an ability to adjust behaviour, resources and technologies used to solve problems. So any factors that stop your organisation being able to change how it does things, or that reduce your resources, will reduce your adaptive capacity. Conversely, if your organisation is open to new ways of thinking or doing things, then your adaptive capacity will be higher.

It is important to understand adaptive capacity, as it indicates the extent to which organisations and communities are able to cope with the pressures of climate change. There is a growing research base on determining adaptive capacity, and getting detailed understanding of the adaptive capacity of a community or organisation often requires dedicated research and analysis.

However, it is possible to get a very generalised estimate of adaptive capacity of communities using a series of indicators such as those collected through the census and available through the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data on a range of indicators are collected during each census, and include a number of variables such as: annual incomes, size of mortgages, levels of education, dwellings, age structures, and skills. Successful measures have been based around a ‘capitals’ approach such as Five Capitals (Ellis 2000) and Four Capitals (Tinch et al. 2015). Essentially these approaches involve determining important capitals— e.g. natural capital, social capital, financial capital— and collecting data and information about these capitals. By considering the strengths and weaknesses in each capital it is possible to assess and monitor changes in capacity. These capitals can be determined through high level state or national data sets (top-down), or through workshops and collection of local information (bottom-up).

5-Capitals-Infographic copy.png

Adaptive capacity is not only related to individuals or communities, but the adaptive capacity of organisations is also important. Adaptive capacity of organisations is determined by:

- economic resources of the organisation

- technology available and used by the organisation

- information and skills within and easily accessible to the organisation

- infrastructure

- the culture or processes of the organisation and whether they enable a flexible approach to problem solving

- the decision-making context within which the organisation works, e.g. the regulatory context- which can help or hinder efforts on adaptation.

Later in the adaptation process, you will need to consider options that can be implemented to reduce vulnerability and risk, and to support communities/organisations to be able to thrive in a changing climate. At this point in Step 2, it is useful to consider options that build adaptive capacity. By considering strengths and weaknesses you will be able to identify relevant options. You will also be able to identify criteria that can be monitored over time to assess the effectiveness of any strategies you implement, and whether adaptive capacity is increasing or decreasing.

Analysing risk and establishing or updating a risk register for your organisation/assets/project

Risk registers are important components of the strategic management of an organisation. Developing or updating an existing risk register enables you to determine the likelihood and consequences of a variety of issues that may affect your operations and the outcomes you seek to achieve. You can create your risk register using the Guidance on the second pass risk assessment as well as the Risk assessment template for recording your gathered information. This process follows a standard risk management framework which is often used by organisations to assess and manage their organisational risk. This involves conducting a risk workshop with relevant stakeholders of your organization to qualitatively measure the consequences of a given climate change risk to your organization (or any other system) and the likelihood of that occurring. Your understanding of the vulnerability of your systems to climate change will now assist you to understand the likely consequence of a given climate-related risk. Qualitatively rating these risks will help you to prioritise your future actions. It is important to be aware and to document all elements associated with uncertainty that could contribute to your risk assessment. These include the climate change scenarios selected.

You are able to identify what management actions are necessary to reduce any risk and to assign responsibility for addressing that risk. Risk registers are often reported on at higher management levels in an organisation and are an important way of engaging with elected officials and Boards to ensure that resources are available to address these risks which can change over time.

It is useful to develop a register of the climate related risks for your organisation and to report on these on a regular basis. Initial information can be generated from the first pass risk assessment, which can then be used to identify how these risks might play out within your organisation. Identifying management options can be high level at this stage, and can be augmented at a later stage when your adaptation planning is completed. Your risk register should be based on the information generated from your vulnerability assessment, which either is already completed or will be completed with more detail as part of this step (see below).

Your risk register should include at a minimum, the following information:

- categories of assets important to your interests

- a description of the risk that a changing climate poses to the asset

- the consequences of the risk on your asset and likelihood

- the controls (existing activities) which are in place to address each risk

- an indication of the level of risk for different climate scenarios or different time frames.

Priorities for developing responses

Priority areas for action (hotspots) can be identified by overlapping areas of vulnerability, adaptive capacity and climate/biophysical changes. A hotspot exists where vulnerability is high, adaptive capacity is low, and climate/biophysical changes are large. Where there is a hotspot, if no adaptive action is taken, the impacts of climate change are likely to be large and potentially costly financially, socially and environmentally.

It is useful to identify hotspots in your area of interest, as they are likely to be the areas where planning and action are of highest priority. Determining and mapping these hotspots enables engagement with affected stakeholders in or around, or with a link to the hotspot areas (where there is likely to be tension or conflict). Identifying hotspots helps support decisions about focussing resources at these areas, identification of options, and engagement around priority areas and options for funding action. The nature of hotspots and hence the appropriate actions to address them may vary. It is important that you document the rationale that has been used to determine hotspots and clarify this when you talk to the community through your engagement activities.

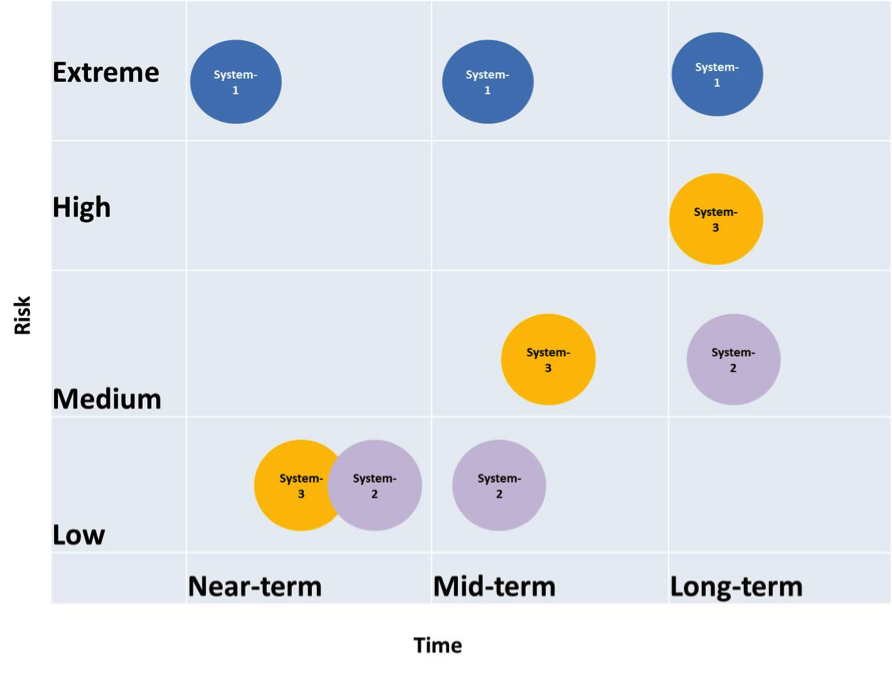

Presenting vulnerability assessments

You can chose to assess your risks at multiple time frames (i.e. short-term, mid-term and long-term). Using the outcomes, you can create a simple graph showing time and risk ratings, and plot the various issues you have identified. This type of graph will give you a visual representation of your risks over time and can help you to decide when action is required, and assist with communicating risks to decision makers (Figure 7).

figure 2 copy.png

Given my vulnerability do I need to update my objective? Do I need to adapt? Do I need a plan? And when should I act?

The outcomes of the vulnerability and risk assessments will provide you with the information you need to extend initial engagement with internal and external stakeholders. It will help determine the extent of adaptation efforts, and consolidate thinking about what sort of plan you need to prepare (building on your initial framing). At this stage it is important to revisit your vision and objectives that you have developed in Step 1 (identify challenges) and ensure they still reflect what you hope to achieve through an adaptation plan. If you have identified new challenges while conducting your risk workshops, it is important that you refine your objectives that you set in Step 1 and include new ones. You should also establish mechanisms to ensure that you get the right buy-in from within your organisation and from outside to ensure that you can develop a plan that will influence all relevant areas of your organisation. If you don’t do this effectively there is a risk that you may develop a plan that will never be implemented, and that your organisation will be impacted by climate change down the track.

Getting a decision to invest in action can be difficult, particularly when it comes to climate change and associated impacts such as sea-level rise. The issues are often complex, the information may be uncertain and the impacts may happen far into the future. There may be inherent social and political biases. Proposed actions may require your organisation to do things differently and therefore meet the resistance that any new idea or change has to overcome.

When faced with the question of what to do about it, people often fall back on the same tactics – make aware, better inform and educate. They hope that these strategies will be enough to convince their decision makers to back their ideas. Experience has shown that there is so much more that needs be done to get buy-in and deliver change.

We provide a guidance manual that will help with Getting organisational buy-in. You need to act effectively on climate-related risks.

Determine thresholds, lead times and decision points for current practices

This step is an important one for the development of your adaptation plan. It recognises that you may have several existing actions, approaches and plans within your organisation, or relating to your asset, that are relevant to your plans to address the impacts of climate change. Your organisation may also have several approaches in place for dealing with current climate risk and vulnerabilities.

It is useful to consider all the existing actions to determine if they are still relevant in a climate-affected future and if their priority should be adjusted (or if they should still be implemented at all). Consider the sequencing of actions and the lead times that may be required for actions, as well as the form of engagement that is required to implement actions. We recommend that you create a simple spreadsheet listing all existing actions. The spreadsheet should include information about what each action or strategy is designed to achieve and when. Each action should then be considered against the climate change scenarios that you have selected to underpin your adaptation plan. This can enable you to determine whether the priority of the action should change or whether there are any maladaptive/unintended consequences which may arise if the action is implemented.

This step also enables you to identify whether there are additional outcomes that can be gained from each action and whether the action can be built on once the effects of climate change become greater. Understanding vulnerabilities and limitations of current practices also helps identify who amongst internal and external stakeholders should be involved in your planning process. Their involvement will help them understand why current practices might have a ‘use-by-date’.

Most adaptation exercises look to go beyond existing practices to meet future risks. But it is important to understand why current practices may be insufficient and when in the future this might be the case. For current practices, think about how much the climate will need to change before you can no longer continue doing what you are doing now. For example, how many times does a city’s main street have to flood in a year before it becomes unviable for small businesses to operate in those situations?

If you do not undertake this step, there is a possibility that you could make adaptation decisions that are not aligned with your existing actions and that you may end up with bad sequencing—or worse— with adaptation actions that may undo certain actions already being supported by your organisation. You may also end up spending more money than is necessary. Importantly, in undertaking this step there may be additional benefits through alignment of all plans in your organisation.

Engaging with stakeholders about vulnerability and risk assessment results

So far in C-CADS (Step 1 and Step 2), you will have gathered a significant amount of information about how climate has, is, and is likely to, affect your area of interest and business. You have used that information to identify relevant stakeholders within your organization and communicated your findings before and during your risk workshop. Although you may be concerned that it is too early to discuss this with your community, this is actually a good time to broaden your engagement activities with stakeholders and the community. In the Information Manual 9: Community Engagement, we recommend starting with a range of existing community groups. By doing this you will begin to build understanding in the community of the issues and the complexity of dealing with them. Information needs to be provided to stakeholders in ways which they can engage with and understand. This clarity is important to build trust with the community. They should be able to understand the methods used and any uncertainties and outcomes and feel able to question methods used and results found. If they do not feel they understand the issues, risks and vulnerabilities, there is a risk they will disengage or feel that they are being treated with disdain. If this occurs it may be difficult to get the support you require to achieve the outcomes you seek. Doing this might raise issues of capacity that you haven’t considered. You might need to consider getting advice on the best ways to engage if you don’t feel confident that you have the skills and resources available.

Be aware also that you are going to need to engage with the community many more times through this process. We explain why it is important to build community support in Building community support.

Checklist for Step 2 of C-CADS

Key considerations in the Determine Risks and Vulnerabilities step |

Yes |

|

Have you considered the guidance on risk assessment in CoastAdapt, and established whether to use a first, second or third pass assessment? |

|

|

Have you considered how you will integrate your risk assessment with organisational risk assessment procedures? |

|

|

Have you determined how sensitive your system is to climate change? |

|

|

Have you considered and assessed the adaptive capacity of your organisation, stakeholders and community? |

|

|

Are you engaging with stakeholders effectively about the risks faced and the next steps that are required? |

|

|

Do you need to revisit step 1 and adjust the framing and objectives of your adaptation planning? |

Critical Success Factors

- Well founded, evidence based risk assessment

- Adaptive capacity of organisation and stakeholders understood

- Informed organisation and stakeholders

Source material

Brooks, N., W.N. Adger, and P.M. Kelly, 2005: The determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity at the national level and the implications for adaptation. Global environmental change, 15(2), 151-163. Accessed 13 June 2016. [Available online at http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.505.7381&rep=rep1&type=pdf].

Ellis, F., 2000: Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford University Press.

IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1132 pp. Accessed 13 June 2016. [Available online at https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg2/WGIIAR5-FrontMatterA_FINAL.pdf].

Tinch, R., J. Jäger, I. Omann, P.A. Harrison, J. Wesely, and R. Dunford, 2015: Applying a capitals framework to measuring coping and adaptive capacity in integrated assessment models. Climatic Change, 128(3-4), 323-337.