You are here

What is adaptation to climate change?

Adaptation is defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as ‘the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects’.

At a glance

- ‘Adaptation’ is defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as ‘the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects’ (IPCC 2014). The definition differentiates between human and natural systems, going on to say: ‘In human systems, adaptation seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In some natural systems, human intervention may facilitate adjustment’.

- Care must be taken to avoid maladaptation – an action that leads to an increased risk from climate change.

- Adaptation planning must take into account the timing of proposed action – because future climate change is uncertain, acting too soon can risk locking into inappropriate outcomes, but acting too late can risk locking into considerably higher impacts.

- There are barriers (which may be surmounted with effort) and limits (which are insurmountable) to adaptation when climate change becomes too rapid or too severe.

Main text

What is adaptation to climate change?

Despite international efforts to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, climate change is likely to have significant effects on coastal Australia. These effects, which include sea-level rise and changes in the occurrence of extreme events, have the potential to significantly impact the livelihoods and lifestyles of coastal residents and the natural environment. Decisions and actions that help to prepare for the adverse consequences of climate change, as well as to take advantage of the opportunities, are known as climate change adaptation.

Climate changes on all timescales from short-term fluctuations such as El Niño events through to glacial-interglacial fluctuations lasting many thousands of years. Humans, and the environment in which we live, have adapted to these changes.

Emissions of greenhouse gases from human activities are just one cause of climate change. These excess emissions are already causing our climate to change, and will continue to have effects several centuries into the future. We are already adapting to these changes and will continue to adapt in the future. However, the rate of change is high and at the moment increasing – this challenges the ability of both human and natural systems to ‘keep up’ – to adapt sufficiently quickly to avoid negative impacts.

Adaptation can happen at any level in society from the individual up to national and international levels. In general, the higher up you go, the more the adaptation responses tend to be policies that frame action at lower levels.

Not all the effects of climate change will be negative, and this is especially true in the early years of warming. However, adaptation may be required to realise any positive benefits. In the coastal zone, for example, tourism may benefit if the climate of rival international beach holiday destinations becomes unpleasantly hot. Adaptations such as improvements to tourism infrastructure, e.g. hotel capacity, will be required to fully realise this potential benefit. As climate change progresses through the twenty-first century and beyond, the likelihood of any beneficial effects will diminish.

The ability to adapt is known as adaptive capacity. Adaptive capacity is defined by the IPCC (2014) as the ‘ability of systems, institutions, humans, and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences’. The important word here is ‘ability’ — just because there is the capacity to do something does not necessarily translate into action. Thus, Australia has high capacity to adapt — it is relatively affluent, with robust institutions and a well-educated and healthy population. But that capacity does not necessarily translate into action to address the risks of climate change.

Definitions of ‘types’ of adaptation

A literature has grown up around different types of adaptation and their definition. Box 1 provides some definitions, and an example of each. Note that an adaptation action can combine different types – for example, it can include both incremental and public.

Box 1: Types of adaptation

Incremental: A series of relatively small actions and adjustments aimed at continuing to meet the existing goals and expectations of the community in the face of the impacts of climate change.

Example: Beach nourishment to maintain the current shoreline and beach quality, and avoid damage to houses on the sea-front, in the face of sea-level rise.

Transformational: Adaptation actions which result in a significant change to community goals and expectations, or how they are met, potentially disrupting those communities and their values. Transformational adaptation is generally undertaken when incremental adaptation is no longer sufficient to address the risks. More information is provided in Transformation.

Example: Relocation of an entire suburb or community including homes, businesses and infrastructure, and abandonment of sea-front houses.

Anticipatory or proactive: Adaptation that takes place before the impacts of climate change are observed.

Example: Local government prevents new development on a greenfield site located in an area likely to be inundated during high tides in 50 years.

Reactive: Adaptation that is undertaken in response to an effect of climate change that has already been experienced.

Example: Individual houses that are upgraded to new building standards only after a cyclone destroys their roofs.

Private adaptation – private benefit: Adaptation taken by a person or business that benefits only that particular individual or business.

Example: Installing a water tank to ensure water availability during a dry spell.

Private adaptation – public benefit: Adaptation taken by a person or business that is of benefit both to that person or business but also to the public more broadly.

Example: Farmer taking action to reduce fertilizer-laden runoff and erosion of topsoil during intense rainfall events}, thus maintaining the viability of his farm whilst reducing the impact on the environment (e.g. coral reef).

Public adaptation: Adaptation undertaken by a public entity to benefit the broader community.

Example: A local government undertakes beach nourishment activities to ensure that the beach is available to the public for recreation despite sea-level rise.

Example: A surf life saving club relocates to a higher position after being frequently inundated by water during high tides.

Timing of adaptation in the context of uncertainty

There are uncertainties around our knowledge of future climate change, especially at the local scales relevant to adaptation policymakers and planners. Although these uncertainties are relatively small for temperature-related events, such as heat waves and sea-level rise, there are greater uncertainties associated with estimates of how rainfall and windstorm will change in the future (see Understanding climate scenarios). In consequence, anticipatory or proactive adaptation runs the risk that the action taken turns out to be inappropriate for the climate change that actually happens. Early action may create lock-in to a determined future pathway, which may be impossible to undo without prohibitive expense and effort, for example, expensive infrastructure that take many years to plan and build, such as flood protection works. This is termed path dependency.

One way to minimise this risk is to undertake no-regrets or low-regrets actions that deliver benefits across a wide range of potential climate futures and/or deliver benefits under present-day climate conditions as well as in the future. One example concerns people who live in flood-prone suburbs. They may take action to reduce their exposure to floods, for example by raising floor levels (e.g. Figure 1). This may prepare them for the effects of future climate change if flooding occurs more frequently.

T4I1_Figure-1.jpg

Climate change unfolds over time with different impacts occurring at different rates. Therefore, we can avoid path dependency and lock-in by taking a pathways approach to adaptation. This involves mapping out the various adaptation options, and deciding where and when the climate change trigger points lie, which will require a decision to be made about whether or not to undertake a particular option. More information is provided in Pathways approach.

Adaptation or maladaptation?

A maladaptation is defined by the IPCC (2014) as ‘an action that may lead to increased risk of adverse climate-related outcomes, increased vulnerability to climate change, or diminished welfare, now or in the future’. Maladaptation results in unintended negative consequences. It may occur for a number of reasons. First, an adaptation may addresses one sector but fail to account for negative flow-on effects in other sectors or to other people’s values (e.g. a sea wall may protect someone’s house but result in the loss of the beach and its amenity values to the community). Second, an adaptation may produce good results in the short term but fail in the longer term— a risk that may accompany many low-regrets actions. For example, a flood mitigation dam built to protect to flood levels anticipated over the next 30 years may fail on longer timescales even though its planned operational lifespan is 60-70 years. Some examples of maladaptation are provided in Box 2. An adaptation plan needs to assess each action being considered against its potential for maladaptation.

Box 2: Some examples of actual or potential maladaptative actions (Source: Noble et al. 2014 Table 14-4)

- Failure to anticipate future climates. Large engineering projects that are inadequate for future climates. Intensive use of non-renewable resources (e.g. groundwater) to solve immediate adaptation problem

- Engineered defenses that preclude alternative approaches such as ecosystem-based adaptation

- Adaptation actions not taking wider impacts into account

- Awaiting more information, or not doing so, and eventually acting either too early or too late. Awaiting better projections rather than using scenario planning and adaptive management approaches

- Forgoing longer term benefits in favor of immediate adaptive actions; depletion of natural capital leading to greater vulnerability

- Locking into a path dependence, making path correction difficult and often too late

- Unavoidable ex post maladaptation, e.g., expanding irrigation that eventually will have to be replaced in the distant future

- Moral hazard, such as encouraging inappropriate risk-taking based, e.g. on insurance or social security net

- Adopting actions that ignore local relationships, traditions, traditional knowledge, or property rights, leading to eventual failure

- Adopting actions that favour directly or indirectly one group over others leading to breakdown and possibly conflict

- Retaining traditional responses that are no longer appropriate

- Migration may be adaptive or maladaptive or both depending on context and the individuals involved.

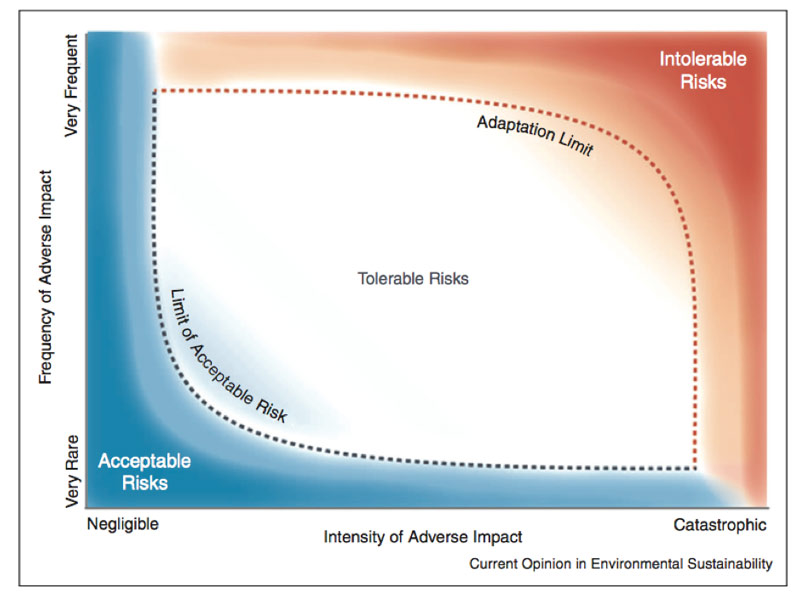

Limits and barriers to adaptation

Adaptation is not a magic bullet – climate change may happen so quickly, or be so severe, that adaptation becomes impossible – either there are no strategies to address the risk, or they become too expensive, or the consequences of the adaptation are considered unacceptable. In this case, the climate change has reached a threshold or limit to adaptation. Limits may be ecological, physical, economic, technological or societal.

An example of an economic limit is where the cost of protecting an asset against sea-level rise by building a sea wall may be acceptable where the level of protection meets the risk over the next few decades, but the cost to meet the risk at the end of the century far exceeds the value of the asset being protected, making the expenditure impossible to justify.

Coral bleaching is an ecological limit. Corals, especially when in good health, can survive a modest amount of warming. But when ocean waters warm by just a few degrees above the long-term average, coral bleaching occurs. A few warm episodes, and there is widespread coral mortality.

The theoretical relationship between risk and adaptation limits is shown in Figure 2. The behaviour of extreme events can be mapped onto this figure and interpreted with respect to risks such as withdrawal of insurance cover. For example, under the current climate the 1 in 10 year flood occurs on average every ten years, insurance cover is available and the risk is tolerable – located in the centre of the diagram. Under climate change, the 1 in 10 year storm may occur every year, and the 1 in a 100 year storm every 10 years on average, causing insurance cover to be withdrawn. The risk in consequence becomes intolerable – moving to the top right of Figure 2.

T4I1_Figure-2.jpg

A barrier to adaptation has been defined as ‘an obstacle that can be overcome with concerted effort’ (Moser and Ekstrom 2010). In fact, the distinction between a limit and a barrier is a fine one, and not always of practical significance. Community opposition to attempts by local councils to zone land at risk of future flooding as unsuitable for development may strictly be described as a barrier, although some councils where the communities are particularly intransigent might term it a limit! More information is provided in Barriers to adaptation.

Linking adaptation and mitigation: realising co-benefits

Adaptation should not be undertaken in isolation, but with an eye to any co-benefits for mitigation, sustainability and, in developing countries, development. Co-benefits are ‘the positive effects that a policy or measure aimed at one objective might have on other objectives’ (IPCC 2014).

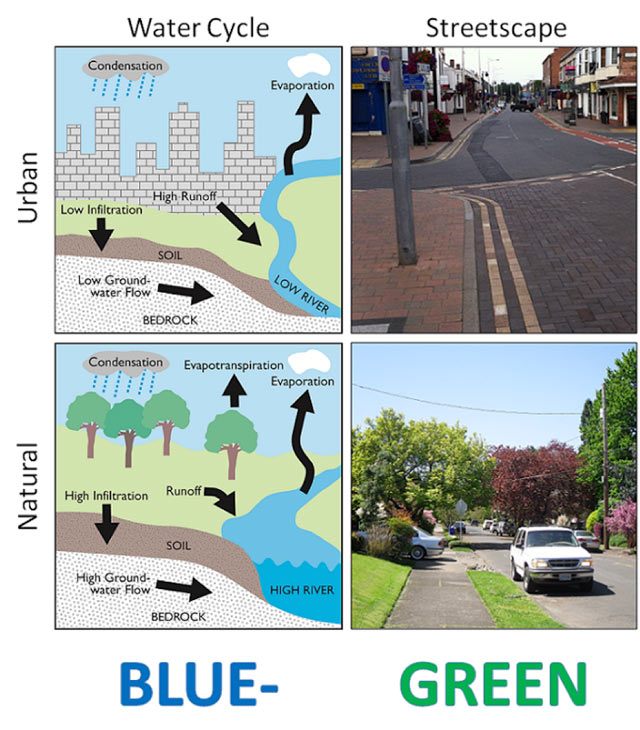

An example of adaptation with co-benefits for mitigation is the move towards ‘blue-green’ cities. These bring together water management and green infrastructure to create more natural urban environments that are adaptive and resilient to climate change, while at the same time sequestering carbon and reducing energy demand (Figure 3).

T5I1_Figure-3.jpg

Source material

Bours D., C. McGinn, and P. Pringle, 2013: Monitoring and evaluation for climate change adaptation: a synthesis of tools, frameworks and approaches. SEA Change CoP, Phnom Penh and UKCIP, Oxford. Accessed 10 March 2016. [Available online at http://www.ukcip.org.uk/wp-content/PDFs/SEA-change-UKCIP-MandE-review.pdf].

Barnett, J. and S. J. O'Neill, 2013: Minimising the risk of maladaptation. Chapter 7 in: Climate Adaptation Futures. Palutikof, J., S. L. Boulter, A. J. Ash, M. Stafford Smith, M. Parry, M. Waschka, and D. Guitart, Eds., John Wiley & Sons, Oxford. doi: 10.1002/9781118529577.

Barnett, J. and J.P., Palutikof, 2015: The limits to adaptation: a comparative analysis. Applied Studies in Climate Adaptation. Palutikof, J., S. L. Boulter, J. Barnett and, D. Rissik, Eds., John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, 231-240.

Blue-Green Cities Research Consortium, 2016: Delivering and Evaluating Multiple Flood Risk Benefits in Blue-Green Cities: Key Project Outputs. pp 1. Accessed 27 January 2017. [Available online at: http://www.bluegreencities.ac.uk/documents/blue-green-cities-key-project-outputs.pdf].

Dow, K., F. Berkhout, and B. L. Preston, 2013: Limits to adaptation to climate change: a risk approach. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 5, 384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.005

IPCC, 2014: Annex II: Glossary [Agard, J., and E. L. F. Schipper, Eds.]. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C. B., V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, and L. L. White, Eds.]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 833-868. Accessed 10 March 2016. [Available online at https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg2/WGIIAR5-AnnexII_FINAL.pdf].

Moser, S. and J. Eckstrom, 2010: A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(51), 22026-22031.

Noble, I. R., S. Huq, Y. A. Anokhin, J. Carmin, D. Goudou, F. P. Lansigan, B. Osman-Elasha, and A. Villamizar, 2014: Adaptation needs and options. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C. B., V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White, Eds.]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 833-868. Accessed 10 March 2016. [Available online at https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg2/WGIIAR5-Chap14_FINAL.pdf].