You are here

Coast and climate dynamics

Coastal development on soft sediments or low-lying areas near the shoreline is at risk of damage from inundation and erosion.

At a glance

- The coast is a dynamic zone where the atmosphere, ocean and land interact.

- Ocean temperature, waves, tides, ocean currents and wind all contribute energy to form and shape the coast.

- Coastal change, resulting from these processes and interactions, occurs on short, medium and long time scales.

- There are two common coastal hazards under the present climate:

- Coastal erosion: Erosion occurs when winds, waves and coastal currents act to shift sediments away from an area of the shore, often during a storm. In most locations this is a short-term process and the shore gradually regains sediment.

- Inundation: During a storm, low atmospheric pressure and onshore winds can cause storm surge and extreme wave heights along the coast. When these coincide with high tide, inundation may result.

- Coastal hazards can result in property damage, loss of life and/or environmental degradation. The impacts are generally greatest where the shoreline has been modified and developed for infrastructure or settlements.

Main text

The dynamic drivers of coastal change

The coast is a relatively narrow dynamic zone characterised by complex interactions between oceanic, terrestrial and atmospheric processes.

The atmosphere contributes the rainfall and temperature that influence the weathering of the land surface and sediment supply to the coast. Temperature and large-scale atmospheric systems also influence sea levels. The wind drives the ocean currents and generates the waves that abrade the coast and move sediments onshore to form dunes. Ocean temperature, waves, tides, ocean currents and wind all contribute energy to form and shape the coast.

These interactions result in coastal change which is a natural process taking place at a range of timescales. These include:

- long-term changes to the shoreline from global climatic change and geological processes, including the 120 m rise in sea level since the last glacial maximum 20,000 years ago;

- ongoing processes of coastal sediment transport, including the supply of sediment from rivers, shoreline erosion or offshore sources, and sediment transport by ocean currents, waves and wind;

- short-term impacts of extreme events such as the landfall of a severe tropical cyclone.

Urbanisation, industrial development and recreational pressures have led to major changes in the coastal zone, with around 85% of Australians now living within 50 km of the shoreline. While many Australian states have established public foreshore reserves, which provide protection to developments located landward, there are differences between state policies and some human settlements are directly exposed to coastal risks.

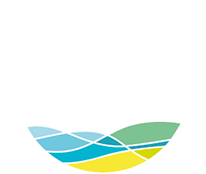

An understanding of dynamic coastal processes, their interactions, and the factors that lead to inundation and erosion, as illustrated in Figure 1, is critical for successful coastal planning and decision-making.

T1I5_Figure-1.jpg

Understanding coastal hazards

The principal hazards of erosion and inundation occur when dynamic coastal processes, often heightened by an extreme weather event, affect the coast. They result in property damage, loss of life and/or environmental degradation. The impacts are generally greatest where the shoreline has been modified and developed for infrastructure or settlements.

Extreme events that can lead to erosion and inundation include tropical cyclones and East Coast Lows (see Cyclone and ECL impacts) and associated high waves, strong wind and coastal flooding. However, erosion can also be a gradual long-term process caused, for example, by the effects of longshore currents that move sand along the beach. Gradual processes, such as sea-level rise linked to climate change, affect the likelihood that these hazards will occur.

Coastal erosion

Coastal erosion is a natural process that occurs when winds, waves and coastal currents act to shift sediments away from an area of the shore, often during storm events. In most locations this is a short-term process and the shore gradually regains sediment over timescales of weeks to months.

In a few locations, coastal erosion has become a problem as a result of human intervention or development near the shoreline. Coastal protection works such as breakwaters, groynes and seawalls are usually built to guard against erosion and protect infrastructure, housing or shipping channels. In doing so, they harden the coast and reduce its ability to adjust naturally.

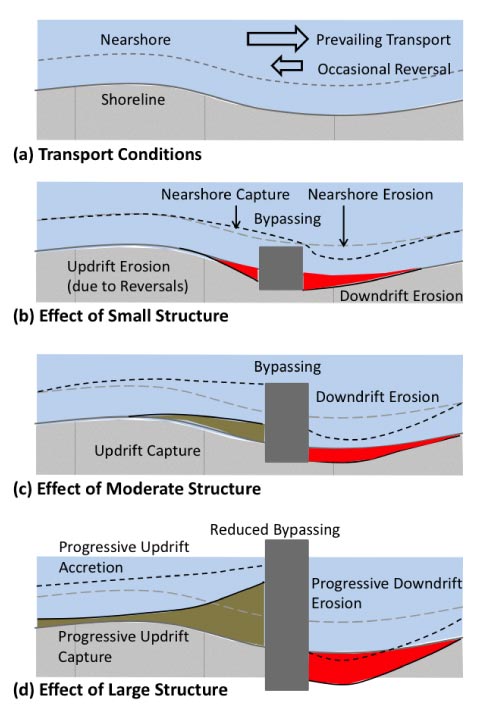

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of coastal structures on the shape of a shoreline where there is longshore movement of sediment. It shows that structures of any size can lead to erosion (red areas), and that accretion can occur updrift of the structure (brown areas), particularly where sediment movement is constrained.

T1I5_Figure-2.jpg

Some examples of these effects are as follows.

- A New South Wales decision in 1962-64 to extend the Tweed River training walls out to sea to keep the river mouth navigable blocked the northward movement of sand to Queensland. This, combined with a series of severe cyclones in 1967, threatened homes, roads and businesses in the Gold Coast (see Case Study on The Tweed River Entrance Sand Bypass Project).

- The artificial opening of the Gippsland Lakes (Victoria) in 1889 increased the exposure of the Lakes Entrance settlement to flooding.

- The development of housing more than 100 years ago at the erosion-prone Collaroy Beach in Sydney has led to buildings in the area being undermined with each major coastal storm.

As the climate changes, the models indicate that tropical cyclones will become less frequent but more intense, which may lead to greater coastal erosion in some areas. In the medium to longer term, sea-level rise is also likely to lead to recession of unconsolidated shorelines, and in this case the loss of beaches will be permanent. Further information on coastal recession can be found in the Information manual on Coastal Sediments, beaches and soft shores.

Coastal inundation

Coastal storm inundation is a natural process that results from the interaction of a number of phenomena.

- During a storm, strong onshore winds can increase water levels close to the coast

- Low atmospheric pressure raises the level of the ocean.

These two together cause a storm surge - a rising of the sea as a result of wind and atmospheric pressure changes associated with a storm.

The storm surge can interact with other drivers to exacerbate the severity of the inundation, these include the following.

- Timing is important – if the storm surge occurs at high tide the effects will be greater; we call this a ‘storm tide’

- Wave height

- The topography of the coastline, including dune height

- If coastal rivers are in flood and the flood water is unable to escape to sea because of high ocean water levels, flooding will be exacerbated in the catchment and river estuary

- During a strong El Niño phase sea levels are lower, and during a La Niña phase are raised around Australia.

As with coastal erosion, human intervention on the coast can exacerbate the risks from storm inundation. The risk of damage to property and infrastructure due to inundation is increased by development in flood-prone areas, removal or damage to natural coastal barriers including dunes, and poorly designed coastal protection structures.

Coastal inundation hazards may also increase with sea-level rise linked to future climate change. Further information on sea-level rise can be found in the Information Manual 2: Understanding sea level rise.

Source material

Kenchington, R., L. Stocker, and D. Wood (Eds.), 2012: Sustainable Coastal Management and Climate Adaptation, CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9780643100275.

Glavovic, B.C., P.M. Kelly, R. Kay, and A. Travers, 2015: Introduction. In: Climate Change and the Coast: Building Resilient Communities. [Glavovic, B.C., P.M. Kelly, R. Kay, and A. Travers A.]. CRC Press.

New Zealand Ministry for the Environment, 2004: Coastal hazards and climate change: A guidance manual for local government in New Zealand. 1st edition. National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

Short, A.D., and C.D. Woodroffe, 2009: The Coast of Australia. Cambridge University Press.